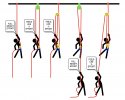

I still need some convincing. In test number one, the climber is pulling his entire total weight with gear (let's say 200 pounds) up the single SRT rope with each pull. Now in test number two, which is supposedly 2:1 now, he runs the rope thru a pulley and back to himself, exactly halving his weight across the pulley on each leg when at rest with no pulling to climb. 100 pounds on each leg, precisely, if we assume a frictionless pulley for now. Now he wants to ascend a bit and adds a little pull to the leg opposite the saddle leg to gain some height. Here is the thing troubling me: whether a single line for SRT or doubled back to himself for MRS, the TIP or TIP pulley still sees exactly the same total weight of climber and gear, or our 200 pounds, all the time. This is a constant and no pulling of any kind anywhere in the system can change that. Whatever he does, the rope will immediately move back and forth over the pulley to equalize. So, if he has real 2:1, and can pull, say, 30 pounds over and above the 100 pounds of half-weight that is always on that leg, so that he has gained twice that or 60 pounds of upward pull subtracted at the saddle from its 100 pounds, then we have an impossibility. He cannot under any circumstances add only 30 pounds down against 60 removed up. There is no '100 pounds lifting 200'. The two legs would not total 200 pounds at the TIP at that instance. What I think he is doing, that feels like great MA, is merely moving the same 30 pounds from the saddle over to the down leg by shifting his body weight over by hanging on the pull down. Thus, instead of feeling his entire 200 pounds as he rises, like on the single line in test one, he only feels the 30 pounds he has to add to one of the equal legs and subtract from the other at the saddle, to raise his 200 pounds. Ironically, this feels actually much greater than 2:1 with 30 applied to raise 200, but is really not MA at all. He has not actually divided the total force needed at all. You have 130 pounds suddenly on the down pull against 70 remaining at the saddle at that instant, he rises and removes some rope from the loop he is hanging on to capture the progress, and the total weight at the TIP has remained his same 200 pounds the whole time, 130 and 70 for an instant instead of the 100 and 100. He has pulled 30 to gain 30 at the saddle. The 60 total difference is just that, a difference, not a total gain. It is the same 30 pounds simply moved to the other leg. And the same amount of rope is actually used, not twice the rope. He moves twice the rope at his hands only because he is also the load and is rising past his own rope moving in the opposite direction. One foot of rope moving up matches one foot of rope headed over the pulley and back down to the ground. As I see it, we may have a neat trick by splitting the climber's weight equally between two legs over a pulley for basic MRS, but I don't see we have any actual MA for the whole work accomplished. He may indeed pull twice the rope with half the force as a groundie each time, to climb, but he is also only moving half the distance each pull that a groundie could give him. His two pulls equal the single one from a groundie, both in distance moved up and also in total rope usage. How is this actual 2:1, except merely seeming to be that at the climber's hands each pull, when in fact each of his pulls is only doing half the job. Further, this means the drawing, with its one single added layer of MA with the pulley moved from TIP to saddle, is just moving from 1:1 to 2:1, not 2:1 to 3:1. We ignore the added pulley up at the ascender since it is not adding more MA and only a 1:1 redirect back down from the TIP to the climber. It may feel 3:1 to the climber himself in the third test but have we really done 3:1 overall? Only twice the rope has moved to the ground, not three times, and he has risen half the distance of rope length used, not one third. The difference involves what the climber experiences against what he is actually accomplishing in the same motion. Consider a driver going 30 mph seeing a car pass him doing 30 the other way. They do indeed pass at 60 but how far has the driver himself actually moved along the road? Or a boat moving up a river to cover 10 miles, against fast river current flowing the other way at 10 mph. The boat has to do 20 mph thru 20 miles of the water moving past him to cover the same 10 of actual distance up the river. Their experiences are valid but are not a true reflection of what they are ultimately accomplishing if they have intended to move a certain distance. As far as I can recall, this is the substance of a discussion between a bunch of experts I was privy to hear at the Sedro Woolley twin-rope thing a few years ago. Mumford was one of the group and I think he could clarify this issue much better in a video (if he hasn't already!!!). The three tests above work as they are said to and felt very convincing to me when I have tried them at times, but don't really tell me the exact amount of mechanical advantage I actually gain.

www.facebook.com

www.facebook.com

www.facebook.com

www.facebook.com