[ QUOTE ]

"Most often, a limb stays in place while CODIT continues and finally breaks near the extended collar of the still living larger limb. For some, this may appear inefficient or disorderly, but it has served trees for millions of years."

Most often..is this based on random observation or imagination or what? How often does a dead branch break off right at the collar?Not very. Open wounds serve other organisms such as decay fungi and bugs, which is also part of nature's plan. but we are here to optimize the tree, which is why we remove dead wood before live wood is infected.

If significant resources are being translocated back from the dead/dying branch to the rest of the tree, then there is reason to hold off on pruning. Except in those rare instances, removing dead wood allows quicker sealing, and protection from pathogens. A very biological reason.

[/ QUOTE ]

I had actually intended to respond to Guy in my previous post, but thought it was more important to reemphasize that we still needed to answer Tom Otto's original question. Having muttered around it in that arena for a while, let me return to a few paragraphs of Guy jousting:

Guy muses that my quote includes incomplete observations or imaginings that unfairly undercut the reasons for deadwood removal. Now I do understand that imagination is a mortal sin for the unimaginative, but it is indeed critical to moving our visions forward and in that process finding new facts and concepts that have never been considered.

I try really hard not to dismiss things out of hand. I think of it as a part of professional discipline that one should listen. Science and mathematics going back to the guys who were trying to figure out just what a number was, are filled with argument and anger to flat-out dismissal of new ideas.

In my previous post, all that one had to do to justify pruning was to waive a page with the printed reasons of "Why we prune". Now a number of those pronouncements are simply embarrassing. Those dogmas and then reconsiderations are always likely to be a part of evolving science. It is also interesting that an awful lot of people think that those facts are at the end of finite knowledge and anything "further" is irrelevant or irritating.

Let me ask some questions of Guy about deadwood:

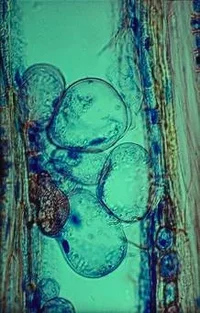

I do understand certain trees anticipating the dormancy of winter will translocate various important compounds back into the woody cylinder near the leaf attachment. I also watched Alex identify areas of starch storage in many different trees by a simple chemical test. Starch was used for storage because it didn't migrate as did the pesky sugars to follow the laws of diffusion and might not want to stay where the tree intended.

Shigo has also said many times that the transformation of stored starch to sugar required a living cell.

Making the assumption that Guy's significant translocation of starches/sugars would most logically be, or most biologically be, back to the parent cylinder such as a limb or trunk. How does that occur if the vessels are being sealed, the internal wood is undergoing a chemical change, and there is an acceleration of the death of cells in the dying limb?

What scientific research can someone share with me that involves say a 10 inch limb, 15 feet long, moving its carbohydrates back to the interface between the trunk and the limb?

There are indeed parenchymal, ray, and other cells that live many years, but that is inside a living operating system. By definition, those cells will be dying and do they, in their time allowed, change starches to sugars and hope that diffusion through the apoplast and symplast pathways move those products the full 15 feet?

If there is in fact a process that relocates important materials to the larger tree from a dying lamb, then when would the limb have finished that process and be eligible for deadwood removal?

(My assumption would be removal before that time would not be a biological benefit for the trade.)

If living cells are required to transform starch to sugar, do we understand their number, presence and role in a dying limb?

I don't mean any disrespect to the discussions and opinions of the posts here, my awareness of other perspectives and conclusions prompts my own questions about what we're told.

-----------------------------------

I don't know quite what to make of Guy's complaint I haven't seen enough or keep to some delusional imagination about how and where trees shed dead and dying limbs. Generally, both the limb and the parrot cylinder contribute to the interface and the interweaving of the gossamer engines at a junction. A dead or dying limb does not add to the structure and only the parent growth creates the extending collar. That collar does not close because the dead or dying limb is in the way.

The isolated collar can only close or "seal" as Guy says it, when the deadwood is gone. Twiggy things and such can get pinched off, but the larger limbs have much of their original strength and permanence still in place. A tree might wait a long time to finally close an old junction.

The 10 inch diameter, 15 foot long limb is a considerable lever and has a significant potential to break at some point. It is also desiccated and subsequently not as flexible as it once was, and cannot distribute a wind or ice loading as easily across its length by bending.

Add to this the probability that CODIT might "weaken" the structural capacity of the limb wood at the junction. The combination of factors suggest something more frequent than Guy's, "How often does a dead branch break off right at the collar? Not very."

Or, as Treebear points out, perhaps the decomposers can concentrate at the expanding collar for their own reasons or take advantage of favorable conditions that the collar might provide. Those conditions could promote pinching or breakage.

Is there a scientific study about where deadwood generally breaks-- either in a forest or in the experience of urban arborists?

----------------

We don't need credentials, or prior approval and permission to ask a question. It helps everyone to have the question reasonably formulated and relevant to the interests of the audience and the questioner. Beyond that it's an adventure, something that we should realize that this freedom is critical to success in our chosen careers. Universities really don't like good questions as they interfere with the process of ladling out possible answers to the expected tests. Students scribble as much down as they can, anticipating what will be in the quizzes and hoping for high scores.

Regrettably, none of this makes much difference after one's first job and it is increasingly unlikely that anybody will ask what was your grade point average in some arcane subject.

I suspect that neither Guy nor I know much at all about points of breakage for deadwood and our factoid fussing ought to be given the boot.

Bob Wulkowicz