That's a great book, Patrick. I have one of the newer ones but yours looks like a first edition.

So, there are a lot of answers that have been listed here, but the one that I was looking for was provided to me years ago by the late Brion Toss, who said the answer to how you get power from a pulley/block and tackle is as follows:

"A block and tackle is either a

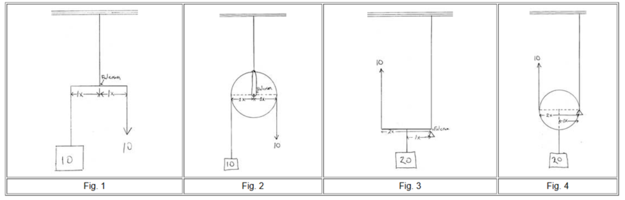

first-class or second-class form of lever, depending on whether the block is moving or fixed in place. If the block is fixed, it is a lever of the first class, in which the

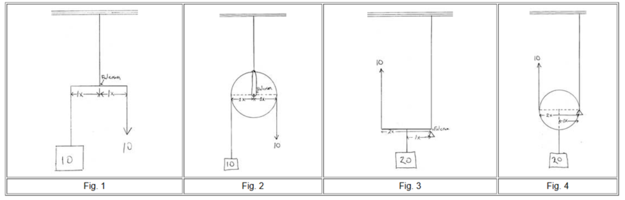

fulcrum lies between the load and the force. The fulcrum is between force and load, so this is a first-class lever. Think of it as a seesaw lever. And since the fulcrum is right in the middle, a load and force of equal amounts are balanced on the fulcrum; the mechanical advantage is 1:1. (See Fig. 1 & 2)

Ah, but look at fig.3, in which the load is between the force and the fulcrum. This is a second-class lever, a "can opener" lever, and in this case the force is twice as far from the fulcrum as the load is. This means that half of the load rests on the fulcrum, so we only have to pick up half the load with the force. Voila, a 2:1 mechanical advantage. Finally, in fig.4, we have a load suspended from a block. The block, in turn, is suspended from a point overhead -- not by its axle, but by a line passing around the sheave. Yup, the same 2:1 mechanical advantage.

That is why we count the parts coming out of the moving block(s), because for each part we gain one part of purchase. That is also why we don't count any parts coming out of a fixed block, because all of those parts simply represent

redirected leads (As in Fig. 1 & 2).

There's a bit more to mechanical advantage gained with block-and-tackle, like the effect of angles, of friction, of compounded purchases, etc. But

the basic mechanism is always the same elegant application of leverage.”

Fair leads,

Brion Toss